New paediatric data mirrors what is seen in adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenia.

The results of a new study should reassure paediatric haematologists that avatrombopag is safe and effective in children with immune thrombocytopenia.

Roughly one in three children with immune thrombocytopenia progress to a chronic form of the disease, where traditional first-line treatment options have inconsistent efficacy and are associated with significant toxicities.

The development of avatrombopag, an oral thrombopoietin receptor agonist, is a significant step forward from other TPO-RAs – such as romiplostim and eltrombopag, which both have limitations preventing their use in a paediatric population.

Although avatrombopag has been proven to be safe and effective in adult with chronic primary ITP and a pair of retrospective observational studies have suggested similar outcomes in children, prospective efficacy, safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data are lacking. Now, the findings of a new international phase 3 trial confirm what was seen in the retrospective research.

“There is a huge need for medications to treat ITP, and chronic ITP in particular. These children often run at very low platelet counts, and there’s a lot of angst about their absolute or perceived risk of bleeding – because even when their bleeding risk is low, ITP chronically affects what activities they can do,” said Dr Melanie Jackson, a paediatric haematologist from the Queensland Children’s Hospital.

“Without treatments to controls their platelet count and ultimately lower their risk of bleeding, they’re often not able to live a normal life.”

Seventy-five patients aged one to 18 years who had been diagnosed with primary ITP for at least six months and had an insufficient response to a previous treatment were recruited from 34 international sites across three cohorts. The first cohort recruited patients aged 12 to 18 years (29 patients), while cohorts two and three recruited patients aged six to 11 years (28 patients) and one to five years (18 patients) respectively.

The 12-week core treatment phase involved once daily (or less) administration of avatrombopag or placebo by oral tablet (cohorts one and two) or oral suspension (cohort three). Overall, 54 patients received avatrombopag and 21 received placebo. Patients in the first two cohorts started at a 20mg dose, while patients in the third cohort started with 10mg. The daily dose was titrated to maintain a platelet count of 50 to 150 x 109 cells/L, with doses capped at 40mg for tablets and 20mg for oral suspensions.

Related

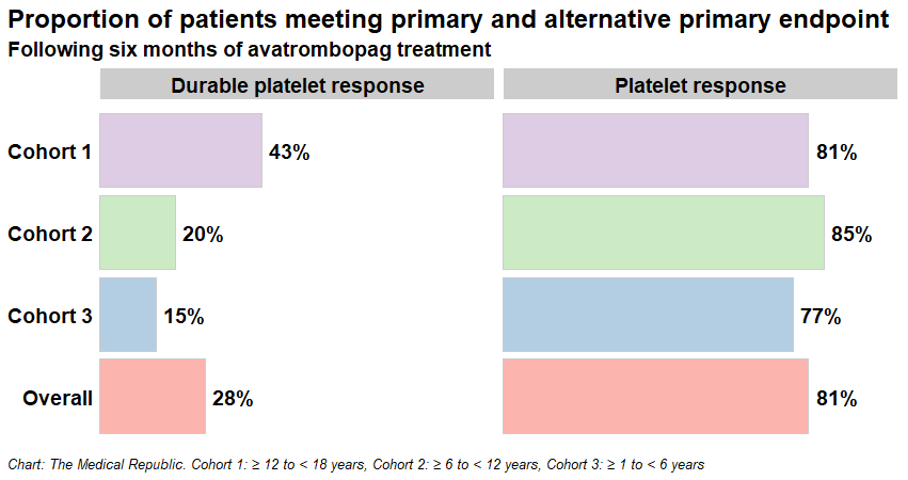

Avatrombopag outperformed placebo on both of the trial’s primary endpoints after 12 weeks of treatment:

- the proportion of patients with a durable platelet response (i.e., having a platelet count of at least 50 x 109 cells/L in six of the last eight weekly assessments without needing rescue therapy; 28% versus 0%), and

- the proportion of patients with a platelet response (i.e., the proportion of patients with at least two consecutive platelet counts of 50 x 109 cells/L over the 12-week treatment period without needing rescue therapy; 81% versus 0%).

“TPO-RAs stimulate platelet production via megakaryocyte proliferation and differentiation by activating the thrombopoietin receptor,” the researchers noted.

Dr Jackson said she was reassured by the finding that 81% of patients experienced a platelet response over the course of the study.

“The way the authors set up the study was somewhat interesting, because it was a little bit different to the protocols that were used in the studies looking at romiplostim and eltrombopag, the sibling drugs for avatrombopag, so it’s hard to compare like for like,” she explained.

“For example, the current study had a lower cutoff for pausing the medication – a platelet cut-off of 250, whereas some of the other studies used 400 as the cutoff point – and they also had a large proportion of patients who had previously failed other TPO-RAs.

“It looks like patients had less of a response to avatrombopag compared to the other medications. But when you look at some of the modified primary endpoints, as well as the secondary endpoints, you can see that patients did quite well on this medication.”

The proportion of patients displaying a platelet response (durable or otherwise) was higher in older patients compared to their younger counterparts, although the researchers emphasised the study was not appropriately powered to make meaningful comparisons between different age groups.

Dr Jackson felt there wasn’t a strong reason to believe that there would be a difference in response rate based on the age of the patient.

“I would like to see the data in a higher-powered study; there is some data from China but not reported in the same way,” she told Haematology Republic.

“But in saying that, we do often use these drugs more in teenagers/adolescents because these are the patients who want to do the activities which put them at a higher risk of bleeding. So, all of these secondary treatments, whether they be immune-mediated or TPO-Ras, would be used more in the older age groups because of the increased need of quality of life activities and the higher incidence of chronic ITP in the older age groups.”

Another point of difference in the approach of the current study was that the researchers used six months in their definition of chronic ITP, rather than the internationally accepted 12 months. However, Dr Jackson felt this was appropriate.

“We should be able to start using these medications at an earlier time point. I have parents who are petrified at [the prospect of] letting their toddler be in the care of anyone but themselves because of the perceived bleeding risk. And while the risk of bleeding is low, it’s not zero,” she said.

“Having these second-line agents available at an earlier time point would be hugely beneficial for our patients with chronic ITP. Studies report that the quality of life of patients with ITP is similar to that of patients going through chemotherapy, so it’s hugely important that we treat all aspects of this condition.”

The majority of secondary outcome measures also favoured avatrombopag over placebo – including the proportion of patients with a platelet response at day eight (56% versus 0%) and the proportion of patients requiring rescue therapy (7% versus 43%) – although the proportion of patients experiencing bleeding events were similar (83% versus 90%).

Adverse events were common across both groups (93% of patients receiving avatrombopag and 76% of patients who received placebo). However, the most commonly reported adverse events – including minor bleeding from small blood vessels, nosebleeds, bruising and headaches – were mild to moderate in severity.

Patients and parents of patients involved in cohort three, which received the oral suspension rather than a tablet, felt the suspension was palatable and acceptable.

“The results of this study suggest that avatrombopag is an effective oral TPO-RA for children and adolescents with persistent and chronic ITP (≥6 months) who have had an insufficient response to previous therapy, resulting in a decrease of treatment and disease burden for patients and their caregivers,” the researchers concluded.

Avatrombopag is currently approved for use in Australia in adults with chronic ITP who have previously had an insufficient response to other treatments, and is used off-label in children with the condition.

“This study is only going to support [the use of avatrombopag],” said Dr Jackson, who knows of many centres – including QCH – that already use the treatment.

“The reason why this medication is the preference for a large proportion of our patients is because it’s not a subcutaneous medication. Whilst some patients prefer [the injections], as then they know the medication is in and then they don’t have to worry about taking the oral medication daily, most prefer oral medications with no dietary restrictions.

“Patient-led decision-making is a big thing in ITP – it’s not just us making the decisions, it’s a combination of us, the parents and families and the patient, if they’re old enough.”